If you open your eyes,

If you open your eyes,

night opens, doors of musk,

the secret kingdom of the water opens

flowing from the center of night.

And if you close your eyes,

a river fills you from within,

flows forward, darkens you:

night brings its wetness to beaches in your soul.

Octavio Paz, “Water Night”

ONE

“Are you sure it didn’t come today?” I asked, trying to appear, and sound, calm and non-chalant.

“Yes, Senor, I checked this morning when you called.”

Why doesn’t this asshole even look up at me… did he even check? I bet he didn’t even check… asshole…

“It is very important to me that you are sure – I’m sorry, it’s just… it’s just very important, do you understand? Es-muy-importante. Nothing for Joe Brian, nothing for doctor Joseph Brian?”

The man nodded his head as if indicating “yes”, but didn’t answer. He was looking down at a computer screen, distracted, and typing on the keyboard.

Son-of-a-bitch isn’t even paying attention to me…

I leaned in close to his face, and slammed my open palm down, hard, on the polished granite counter – WHACK!!

I NEED YOU TO BE SURE, GODDAMIT! PAY ATTENTION! PAY ATTENTION TO ME ASSHOLE!”

His head came up and his hands jerked back from the computer keyboard as he moved back quickly from the counter. His dark brown eyes were wide with surprise and confusion. A door behind him flew open, and another man leapt out, wearing what looked to me like a security uniform designed by Walt Disney – turquoise short sleeved shirt and long pants with orange trim piping, replete with a gold star-shaped badge on his left chest pocket and the right tricolor floral logo of this place on the right.

I noticed that he wasn’t carrying a gun, or any other obvious weapon.

Why am I looking to see if this guy is carrying a weapon…? What am I doing?… Jesus.

I looked down at the floor, and shook my head in self-disgust.

After an awkward moment, the desk receptionist regained enough composure to speak, in a trembling voice tinted with both fear and what I was certain was resentment of me – just another “ugly American tourist. “Senor… senor please… please do not raise your voice…, this is… this is disturbing the other guests.”

I turned my head and looked behind me. The lobby of the exclusive Cancun resort, a three stories high round, thatched roof structure, open-air on all sides, was filled with vacationers, most clad in expensive resort wear – a colorful and slightly disorienting cacophony of clothing – palm leaves, parrots and beach umbrellas. Several of them had stopped in their huarache-sandaled tracks and were now looking at me more with curiosity and expectation than with fear – as if I were just another form of resort entertainment. A sunburned cherubic toddler in a stroller, wearing a blue-jean sailor’s cap emblazoned with a red and white striped “POLO” across the brim started crying as his mother, who had been in line behind me, backed away several steps, stumbled, and almost fell down as one of her pink and white rubber sandals folded over on itself.

“Sorry… I’m sorry,” I said, while still looking at the mother and the crying child. I then turned back to the receptionist and the security guard, lowering my voice as much as possible, just above a whisper, motioning with my shaking hands for effect – “really… I’m sorry, it’s just that I checked online this morning, and the Fedex site told me that it… my package… had been delivered here yesterday… that’s all… sorry. I thought for certain it had arrived. That’s… that’s… what the online site said…”

The security guard had inched back a bit toward the still open door behind him, but didn’t give the impression that he was about to leave. He was swarthy, with a thick black moustache, and what I guessed was a more or less permanent five o’clock shadow. The brim of his baseball-style cap, also turquoise and orange, was pulled down so low I couldn’t see his eyes. I smiled at him feebly, but his expression, at least the part I could see on his lower face, didn’t change.

I glanced to my far left and saw that another man, this one dressed in a fitted dark suit and tie had walked up to the end of the reception counter. He was wearing one of those secret-service type earphones, and was staring at me ominously. His left hand was resting on the counter and his right arm was across his chest, with that hand out of view far under the lapel of his coat. I shook my head again and chuckled nervously to myself.

What do you expect for a thousand bucks a night…?

Ascertaining that I was probably more of a nuisance than a threat, the receptionist by now had completely regained his confidence – looking past me and smiling at other guests, and nodding to indicate that all was well. He then reached out and patted my hand.

“Senor… senor… please… you look terrible. Perhaps you should consider seeing the doctor – we have a doctor here twenty-four hours a day, and a very good one. Please, may I call him for you now? It is no trouble. Con su permiso? It is no trouble, really, senor, I insist…”

I looked in the mirrored wall behind him, at my reflected image. My thinning hair was unkempt – uncombed and unwashed for several days. Even from this distance, and with blurred vision it was also obvious that there was a several-day beard, sunken dark-circled bloodshot eyes, and an ashen-grey swollen face. No wonder my family was so worried.

“NO!… I mean, no… no thank you… I am a doctor, actually… I just have the flu, that’s all. It’ll be okay, please forgive me… so sorry…

I glanced nervously back at the secret service-looking guy again, and then turned and walked toward the elevators, wiping my nose, which was running profusely. My eyes were watering so badly that I had trouble finding the up/down buttons on the wall. Although here were a couple of other people waiting for the elevator, they elected to let me ride alone. Once the doors closed, I lifted my arm and sniffed… I wouldn’t get into a tight space with me either right now…

I found the magnetic key in my pocket, and opened the door to our room – a big two-bedroom suite overlooking the azure Gulf of Mexico from five stories up, replete with a five hundred square foot balcony, a full dining room and well-stocked wet bar.

Thank God they’re already at the beach…

I fell onto the bed… The sensations that came with this particular illness, which in fact was not the flu, were strange, but I knew them well. My skin felt uncomfortable and tight, as if it didn’t fit my shape. My bones ached – really bad, and it seemed that… if I could just reach in, grab them one at a time with my hands, and squeeze the blood out, squeeze the blood out… that they would stop hurting.

I got up and stumbled into the bathroom where I fell down onto my knees in front of the toilet. Curiously, even though my kneecaps struck the beautiful dark green marble floor with enough force for the dull popping bone-on-something-solid sound to echo around me, it didn’t hurt, or at least there was no sensation of pain – a wavefront of nausea was occupying my sensorium at that moment. I had a habit of counting things – “a touch of obsessive compulsive disorder”, a psychiatry colleague had once suggested during my residency training… I stopped counting the number of times I had retched after eleven.

I let the crown of my head dip into the water and vomitus – goddamn that’s cold… It occurred to me that I might be able to submerge my entire head and drown myself, but I knew I would pass out and fall away from the bowl, only to be found later by my wife and daughter, who would then take me to a hospital and find out what I couldn’t let them know. I slumped back, straddling the base of the porcelain bowl with my legs and extending my arms upward to grab the seat-ring on either side and hold myself up. I could see my reflection in the shower glass-door. I looked like a crazed street person trying to ride a bathroom toilet bowl chopper-bike. I thought about laughing for a moment, but couldn’t.

I’ve got to get the hell out of here…

Although it wouldn’t have been obvious to anyone if they walked into my hotel room at this particular moment – I was a famous surgeon… a small-town Texas sports and academic prodigy who grew up as the only son of parents that didn’t finish high school. I had been an undergrad at Duke University, where I lettered in two sports, then on to Harvard Med, and following that, a Mayo Clinic surgical trainee. I was now on staff at one of the top medical schools in the country – promoted to full professor by age thirty-seven. I was by all measures on the very top of my game… I had the respect of colleagues worldwide, spoke at expert conferences, and made close to a million dollars a year. I operated on homeless people and world leaders, saved many lives in the process, and comforted the dying and their families with compassion when that wasn’t possible… I was married to a brilliant, beautiful woman, and had one child, a daughter that was the love of my entire life – my sweetheart… my everything. I was with them now, on vacation for the first time in three years, at the most exclusive resort property in Cancun.

I was also hopelessly addicted to pain medication – narcotics. On a good day, I took enough of them to kill ten people. Unfortunately, due to a combination of improbable and unfortunate recent events – I hadn’t used for more than ten days now, and as a result was in full-blown, life-threatening opiate withdrawal.

I crawled out of the bathroom on my hands and knees – both coated with what had should have remained in my gastrointestinal tract, but had found its way to the outside world – I had evidently missed the toilet a few times. As I moved forward, my sticky hands made a “THWICK, THWICK” sound as they first stuck, and then lifted up from the floor. I grabbed the edge of the bedspread, pulled myself first to my knees, up onto wobbly legs, and fell face first onto the bed.

My usual supplier had promised me that he would get me Oxycontin two days before we were to leave for vacation, but had never shown up in the hospital lobby at the time we had agreed to. This was highly unusual – he hadn’t missed a drop in six years. I assumed that he had either been arrested or killed – you weren’t able to support a habit like mine for twenty-plus years unless you had seen several of your sources come and go. None of them were brilliant. In the end most were either too greedy, or used too much of what they were selling themselves, and eventually made mistakes.

I on the other hand, if not brilliant, was very, very careful. As was the case with my career in surgery – I did not make mistakes, and always had a backup plan. I had bribed a local, financially-strapped elderly primary care physician to falsify some records indicating that he was treating my wife for a gynecologic condition which included unremitting pain – I even told him exactly what to write in her fake record, giving him all of her medical history and even telling him where her few minor physical imperfections, moles, etc., were located, to make his documented – but never actually performed exam – ring true…

…“DIAGNOSIS AND PLAN: Gravida-one para-one Caucasian female with probable severe endometriosis… suggested hormonal therapy, but she refuses due to previous adverse effects, including possible pulmonary embolism. She asked to provide pain medication to be used during the perimenstrual period on occasion when necessary, has used non-steriodal meds without good result, and episodic opiate administration seems reasonable at this time… She has signed an opiate treatment contract and has provided a negative drug screen”

I kept him on a healthy monthly retainer – for insurance against events just like this – “on call” for me, if you will. He was only clearing about a hundred thousand a year and had three divorces and a young girlfriend to maintain – he was a ridiculously easy sell.

According to the Fedex tracking system, which I had pulled up on my laptop in the hotel room thirty or forty times the past two days, the old bastard had evidently held up his end of the agreement, but the package never arrived. As a result, someone working at the resort mail room was having a party, and I was dying, listening to marimba music and the laughter of children at the pool waft up from below and into my open balcony doorway.

§§§§§§

TWO

At least I have a prescription for this one… I gulped a sleeping pill down with a mouthful of gin and tonic – one that would put most people out for eight hours or more – put my head back on the first class seat headrest, and woke up a couple of hours later.

The guy sitting next to me poked me in the arm with something – hard. I jerked my head forward, and blinked my matted, constantly watering eyes several times before they adjusted to the dim light in the plane. I had the distinct impression in my disoriented state that it had been the barrel of a gun, but it turned out to just be his Ipad.

“We’re here man, flight’s over” he said, “Jesus… I hope you’re feeling better, you look like hell.”

I looked down at my lap – there was an airsickness bag more than a third full of fluid. I had evidently thrown up into it at sometime during the flight, but had absolutely no memory of it. It reeked. I reeked. I mumbled an apology.

I had only been able to keep down a couple of pieces of hard candy the night before, and the smell wafting up at me now – gin and strawberry mixed with vomit, reminded me distressingly of Bourbon Street in New Orleans, where I went at least once a year for a medical conference – the smell of “recycled” Hurricanes on the pavement. Judging by the tense, angry stares of the other passengers in first class now filing past me to disembark, I wasn’t the only one who noticed.

I had convinced my wife to stay at the resort the last several days of our planned vacaction, as the… “room is paid for, and you know it cost a fortune… really, you and Maria enjoy yourselves, and I’ll go back and see someone in the medical center – better than getting admitted to some crappy hospital in Cancun… It’s just Influenza, that’s all… just a bad case of Influenza… some intravenous fluids and some meds and I’ll be good as new…” Amazingly, even though obviously worried, she had agreed.

I stumbled through customs. As I waved my passport by him, the customs agent asked, in a matter-of-fact tone, “Montezuma’s Revenge, Huh?”

“Yeah, something like that,” I stammered, cleaning my nose with the sleeve of my wrinkled dress shirt, which was caked in dried mucous from a thousand previous wipes. I grabbed my bag from the luggage carousel, found my car in the parking garage, and plugged in my phone – I had a couple of very important calls to make.

I called in a one hundred eighty milligram tablets of Oxy at two different pharmacies. I used the old doc’s DEA number and his office phone, and used my wife’s name on the prescriptions. I was taking about six of these a day, on average – this would last me a while. No mistakes…

I knew that I was dehydrated, and dangerously close to needing to be admitted to a hospital, but that if I could get one dose down that I would be much better in a few hours – I picked up a Gatorade at a news-stand on the way out of the airport.

Once through the first pharmacy drive-through, I pulled my car into an adjacent apartment complex lot. If you are in withdrawal, your body really starts to freak out once you know you are about to use again – you start shaking all over, and your eyes water so bad it’s almost impossible to see. I struggled to get the child-proof top off of the bottle… I hit the steering wheel hard with my hand grasping the bottle – “C’MON GODDAMIT, I NEED THIS!!!” I rolled my window down, took a couple of tremulous deep breaths, and focused again on getting the lid dislodged.

Finally…

I took two tablets out and put them in an extra large coffee cup I kept in the car for this very purpose, just big enough for my Iphone to fit inside. I used the top hard edge of the phone it to grind the tablets into a coarse powder, with great difficulty – I was shaking so badly that the phone rattled around in the cup sounding as if I were playing some weird percussion instrument completely out of time with the music that was blaring out of the car stereo – whatever that was, I was almost incoherent.

“C’mon… Shit… C’mon baby… GOOD ENOUGH!!” I opened the Gatorade and poured some of it onto the powder, sloshed it around, spilling a little on my pants “GODDAMIT!!” The drug wasn’t soluble in the cold liquid, so most of it collected on the top of the green fluid, some of the larger pieces floating around on the top – they reminded me of little tiny lifeboats circling a whirlpool… they are lifeboats… I put the cup to my lips, and…

Yes… yes… thank you, God… thank you… yesss… Jesus… yesss

I put my head back on the headrest, and then fell asleep sitting there in the apartment complex parking lot for an hour or so. When I awakened, I felt a little better. I knew it would take three to four doses to get my blood level where it needed to be, but it was amazing how one big hit could bring you back from the brink. I could actually hear the music now, and put the satellite radio on my favorite channel. I drove through the second pharmacy pick-up window and obtained the second prescription. I tore it out of the paper bag, counted the pills by turning the bottle around and upside down, and threw it into the passenger seat with the other bottle. It dawned on me that I wasn’t expected back at work for more than three days – I would have plenty of time to recover. I’m gonna take all of this shit… As I drove out of the pharmacy parking lot, a warning light blinked red on the dashboard, and I remembered that we had been a little low on gas rushing to the airport days earlier. Not a great part of town, but I probably should pull off and get some – Don’t want to run out of gas and risk having to deal with a policeman right now…

I took the the next exit and pulled into the first gas station I came to on the service road – one of those tiny ones – a couple of islands and a ten by ten foot “store” where the clerk was stationed. This one had an iron grate over what looked like a bullet-proof window for customers after dark, at which time the door was probably chained closed. From a distance, it looked as if the main items for sale inside were condoms, tobacco and beer.

Really great neighborhood…

I opened the car door and looked at the pump – it didn’t have a credit card option, so I walked over to the clerk, and went inside. He was a young man, no more than twenty I guessed, and middle eastern.

“Give me thirty, please”

“Thirty dollars? Pump four, sir?”

I looked out at the pumps. My car was the only one parked outside. I looked back at the smiling young man with a bit of incredulity. “Uh… yes…”

“Very nice car, sir”

“Thanks”

“Is it expensive?”

“Yeah, I guess so.”

As I walked out, he followed me to the metal and glass door, and stood there looking at the car.

I noticed that when I had got out of the car, I had left the driver-side door open, so I shut it, put the pump nozzle in the receptacle, and put the thirty dollars worth into the tank. I was feeling better all the time, even a little giddy as I plopped into the car and closed the door. Then I looked over at the passenger seat.

Didn’t I leave the bottles sitting here?

I felt the first twinges of physiologic panic, cutting painfully through the narcotic-induced calm of a few moments earlier like a shard of sharp glass – the noticeable quickening of the heart rate, and the little brightening of your field of vision as the pupils transiently dilate in response to the adrenaline as it is squeezed out of the adrenal glands, and into the bloodstream… I looked in the floorboard – nothing. I yanked open the glovebox – nothing.

“SHIT!!!”

I jumped out of the car and ran around to the passenger side, yanking open the door, looking in the space between the seat and the doorjamb – nothing.

Then it hit me…

Did someone take them? Someone took them… Someone stole them… “GODDAMMIT!”

I raised up quickly, and scanned the horizon. It was early afternoon, and there was no one walking around. This was a fairly desolate stretch of service road – a couple of abandoned and dilapidated old buildings on either side, a greasy chicken drive-through a half block down, and this crappy little place. I looked again at the service station building, the clerk was still standing at the door, watching me. Then, I noticed a door on the back right hand side of the building slightly ajar – a bathroom?

I ran around the front of the car, pulling myself around the last gas pump to keep from slipping on some loose gravel. I got to the bathroom door, grabbed it and yanked it completely open. There was someone inside, someone standing at the sink with his back to me.

“What the fuck do you want?” he said, turning his head slightly and looking at me over his left shoulder. He was peeing in the sink, holding his penis in his right hand. He had the characteristic odor of a street person, and was wearing a tattered military jacket with the sleeves cut off. He had very long, stringy hair and a patchy, untrimmed beard. His left arm was hanging by his side, and I could see needle tracks all up and down its length, some fresh, from the door… and in his left hand were two large bottles of pills.

“Get the fuck out of here before I kill you, fuckhead” he said, coughed, and laughed.

I snapped.

I leapt into the space with him, and grabbed his hair, yanking him around to face me, his penis still hanging out of his fly.

“SHIT MAN, GET OFF ME! I’LL KILL YOU!”

He was emaciated, and I was bigger than him, by maybe a hundred pounds. I pushed my body hard into his, and his lower back bent at a bad angle over the sink behind him.

“SHIT, MAN! MY FUCKING BACK!”

He dropped the bottles, and reached into his left pocket. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see him pull out a huge pocket-knife. He struggled to open it, but couldn’t with one hand. I was leaning in hard, and had him crowded into the sink bending over backwards – my chest and abdomen in contact with his. He couldn’t reach around me with his right hand.

He started hitting me on the back of the head with the butt of the knife, but he was too close in once again to generate much force.

I impulsively reached for his throat, and everything slowed down at that moment… way down – and it felt as if I were watching, but not actually doing… not actually involved.

I knew exactly where to grab – I know the anatomy, I know the anatomy, goddamn you… I knew how to kill him… to kill him… kill him. I grasped his neck between my thumb and fingers – hard, hard, harder. Twenty years of surgery had left me with an incredible grip. His neck was thin and the skin loose, and my fingers dug deep into his flesh and found the space between the large strap muscles and his trachea. He tried to grab my hair with his right hand, but couldn’t get a grip – it was too short.

I tightened my grip on his carotid arteries, which I sensed were being pressed up against his firm airway in my grasp, and I felt his body beginning to lose tone, lose interest in the fight – I was cutting off the flow of blood to his brain… Kill him… Without loosening my grip, I let my hand slide up higher his trachea, right below his thyroid cartilage, and squeezed harder… harder… harder. I felt the cartilage in his upper trachea crack, and crack again. I readjusted my grip and it buckled and cracked a third time – it felt like hard kernels of popcorn being crushed in my hand. My face was no more than an inch from his… His eyes bulged, his tongue protruded like it was about to be completely expelled, and thick, dark bloody foam bubbled out of the corners of his mouth.

I let go of him.

He dropped to the urine-soaked maroon concrete floor, grabbed at his throat with both hands, let out a couple of pitiful squeaking sounds, and passed out. I stood over him and looked at my watch. I had to think about it to notice that I was panting. At the three minute mark – I counted all one hundred and eighty seconds – I reached down picked up his wrist. There was a faint, very slow irregular pulse. He wasn’t dead, but he was about to be.

I picked up the bottles and walked to my car.

§§§§§§

THREE

Context… we see the world through its prism – the familiar patterns and known colors of refracted reality. What we expect to see, and what we feel we need to do in any given environment is shaped in part by the environment itself – it’s one of the main ways that we make sense of the world. In actuality; however, context is nothing but a setting – a theatre for events, and not the events themselves. Even though it is theoretically unlinked from “what comes next”, it is what we use to orient ourselves, and predict what will or should occur.

For example, even though it is entirely possible, you don’t expect to see a clown in a morgue – it would be disorienting. You wouldn’t expect a high school marching band to play a fight song at a daytime church funeral, or to find exotic dancers performing at an elementary school open house to throbbing loud hip hop. You might not expect to see a well-dressed surgeon strangling a heroin addict to death in a seedy bathroom in a really bad part of town, or two flak-jacketed city policemen and a state trooper walking into an academic medical center outpatient surgical clinic with their guns drawn.

I was arrested four days before my wife and daughter returned from vacation. The fact that I had seen them for the last time as a free man, through bloodshot and watering eyes at some glitzy, overpriced resort in Cancun, didn’t even cross my mind until the arraignment – I was just worried about having to go through withdrawal again, and scheming how I might get Oxycontin in jail.

The trial was short, accelerated largely by the fact that I pled guilty. My lawyer – a very expensive criminal attorney from Dallas that wafted a transparent cloud of Polo cologne in a twenty foot radius around his body, and whose hair seemed like a plastic appliqué, had convinced me at first to plead not guilty due to temporary insanity related to narcotics use. He even produced an expert witness that said that “the huge amount of Oxycontin Dr. Brian was taking had to have changed his brain chemistry and function, and therefore, changed his behavior”. I agreed with all that crap, but I freely admitted that I killed the guy – I was climbing out of withdrawal the whole time the proceedings wore on, and just wanted to get the whole incredible hopeless mess behind me. Of course, despite the expert witness’s fine testimony about my neuroanatomical derangement, at the same time that I killed a man with my bare hands due to bad brain chemistry, I was also performing complex surgical procedures, and leading what appeared to everyone else to be a normal, enviable life.

My mind wandered a lot during the trial proceedings. I knew that it was a pro forma exercise once I decided to just get it over with, and that the only question was how bad the punishment was going to be – so why pay close attention?

I hadn’t thought about how I got hooked on the pills for a long time…

I knew a lot about addiction due to my background as a physician – and even though I wasn’t really listening to most of what he was spewing out at the jury for what was likely a five hundred dollar an hour human rental fee, the expert witness’s nicely rendered diagrams jogged my memory on the topic. The opiate family of drugs, which all mimic to some degree the parent drug morphine, are little molecular structures that want to bind, or stick to / into another molecular structure somewhere. The things that drugs want to bind to are called receptors. When I was a medical student, it helped me to think about drugs as keys, and receptors as locks that they fit into.

The receptors for opiates are located in many places in the human brain, but most importantly in the anatomical areas where we sense reward and pleasure. Taking an opiate, to the brain, is like having a piece of the best New York pizza known to man after two days of fasting, or having sex at age 25 after a long hiatus – it’s a neurochemical event that the brain “remembers”, and wants to experience again if possible. Another way to think about it is that the drug molecules and receptors aren’t keys and locks at all, but rather sexual organs – each dose leads to a billion-billion penetrations as the drug finds its targets, and a billion-billion molecular climaxes – the brain’s pleasure is intense.

If you take them often enough, the brain begins to want to experience it again, over and over – who wouldn’t want a billion-billion climaxes? The expert witness was right, at least in part – some of the chemistry and function of the reward system nerve pathways in the brain do indeed begin to change over time such that the drug is expected, not just desired. However, it is important to note that there is a sinister thing happening as you begin to use opiates more frequently that sucks you in at the level of not only the brain’s reward and pleasure pathways, but of the brain’s very cells, your own personal biology as well. As you take more opiates, and as they get into the brain and bind to the receptors, the number of receptors in each brain cell decrease – requiring that you take larger and larger doses to get the same effect.

During my senior year in high school, and against my father’s best judgment and expressed wishes, I bought a used lime-green Suzuki 250cc motorcycle with the money I had saved up from a job the summer before. On a rainy day in April, on a Farm-to-Market road a few miles outside of my town, I skidded going around a corner doing eighty, and hit a truck broadside, breaking the femur in my left leg cleanly in two. I still remember the pain – like someone had ripped my upper leg in half, poured hydrochloric acid on both raw ends, set them on fire, and then for the next hour, tried to put the fire out with baseball bats. The first dose of intravenous morphine in the emergency room was my first experience with a billion-billion climaxes – I never looked back.

In college, it was relatively easy to score pain-killers. At the state university, you didn’t have to walk more than a hundred feet to find someone that knew a source. Even though I was waist deep in my addiction by my sophomore year, I impressed my parents a great deal by holding down a job and making close to a 4.0…

“…we are so proud of you son, and all the initiative that you are showing”….

What they didn’t know was that I was holding down a job only so that I could buy drugs.

As the years passed, I became an expert in finding, buying, and concealing narcotics. As you become a hard-core addict, the “external” signs of abuse – lethargy, mood changes, and so forth, decrease over time, so as you use more, it becomes easier to hide it physically. My brain was a neurochemical sex fiend – a second, needy and controlling organism housed in my skull. The rest of me – surgeon, father, husband, man – only existed to find, buy, and conceal drugs for him. I didn’t take care of patients out of any sense of responsibility or altruism, I took care of patients so that I could buy Oxycontin. I didn’t take my daughter to her soccer games because I enjoyed the experience or felt responsible, I took her so that people would think I was a normal, loving Dad, and not an addict. I didn’t lay down in bed each night next to my wife because I really wanted to have a relationship with her, I did it because I needed her to help me maintain the relationship with the being in my head.

Based on their buying the expert’s argument, and my clean record, the jury was merciful – rather than sentencing me to death by lethal injection, which is the third most popular sport in the state of Texas behind college football and running for president, they just gave me 70 years with a chance at parole in 35. The judge added six months up-front in a prison drug rehab facility. I celebrated my forty-forth birthday during the proceedings – the math really sucked. I only turned around and looked at my family sitting in the gallery behind me once – it was just too much. I didn’t need to see them to know what I had wrought – I could hear my daughter’s quiet, stifled sobs and muted whimpers behind me each day, all day long, as I sat at the defendant’s table with my legal team. It was an ancient, heavy oak desk – I had purchased a few antiques over the years, and thought that it must have been at least fifty years old, if not more. At first I wondered why the surface nearer the middle aisle, where the lawyers sat, was smooth and polished, and why the area in front of me was so worn – the finish scratched and pitted. It became obvious.

I did manage to convince myself to glance at them out of the corner of my eyes as they led me out of the courtroom, but wish I hadn’t. My wife’s face was stern, and unemotional – I had expected that. This represented many things to her other than losing her husband, whom she now knew she never really had – among them were betrayal, lies, and economic upheaval. We lived well, but we lived from large paycheck to large paycheck – life as she had known it, and had expected it to be forever, was lost.

My daughter looked distraught – her face was wet with tears, and her cheeks red with confusion and shame. Her hands looked so small at that moment – at her mouth, fingers trembling. Maybe I never really did love my wife, never really knew her – the being inside of my head wouldn’t, couldn’t let me have another real adult relationship. However, he did not keep me from loving my daughter – loving her since the first moment I had held her tiny fragile form in my arms.

An incredible wave of guilt washed over me, and my limbs literally went limp right as the bailiffs stood me up out of my chair. Without hesitation or emotion, they grabbed me hard, under each armpit – simultaneously propping me up, and moving me methodically toward the door. It struck me that this was a short walk they had made thousands of times – the distance from the desk where I had sat the past few days, to the exit at the back of the witness stand. I counted their steps as they drug my feet along – twenty-seven… twenty-eight… twenty-nine. I would only make it once.

The needle would have been better.

§§§§§§

FOUR

People like to say that they “fall into” routines, as if there was some sort of gentle gravitational process that effortlessly moves you from one situation or place and into another. However, by no means is that the way it works in prison. There is no falling, or easing, or sliding, or transitioning “into” anything.

Steel is wrought into its various final forms by the process of “extrusion”. The metal is heated into a semi-solid state, and then forced through an opening of a particular shape, with the metal taking on that shape, in a linear fashion, on the other side. For example, a square opening gives you a long rectangular piece of steel, and a circle gives you one that is cylindrical. The way you adjust to prison life is similar to this process – and there is nothing gentle about it. The thick doors of the prison walls are the opening through which you pass to take on another form – to move from the life before, to the life now – to be shaped into what you are now from what you were then – you are extruded.

I was surprised by the fact that the other inmates already knew a lot about me before I arrived. I came to know that this was the normal situation – information provided by newspapers, friends and relatives on the outside, as well as what the guards and trustees knew ahead of time. Although I didn’t know it, and as luck would have it, I had three things going for me.

One, I was a doctor, and for various reasons, many of the other prisoners still had some residual respect for that. I could perform a little first aid from time to time when access to the infirmary wasn’t possible – but that wasn’t what was valued most from “Docky”, as I came to be known. What was valued more than what I did was what I knew. Many of the inmates had parents that were ill, and every now and then, there was a medical issue on the outside with a brother, sister, spouse or child. I was more or less a source of free consultation, advice and at times, condolence.

Interestingly, what was most appreciated was the “truth” – even when the news wasn’t good – they valued greatly my ability to tell them what to expect with the things that they worried about at a distressing distance – the father with metastatic lung cancer to the bones and brain, or the grandmother with a hemispheric stroke that couldn’t come off of the ventilator, or a small child with strep throat. I found an unexpected parallel to my previous discussions with cancer patients as a surgeon, and my discussions with these men. Cancer patients will often be relieved when they get the news – when they finally understand what they are up against – when they can give the tumor a name – when they finally “know”. One of my medical school professors used to say that it is not the fact that the monster is coming for you that is most troubling, but that it is hiding in the dark, and you don’t know what it looks like, and can give it no name. Both groups are often characterized as desperate – these men that I was imprisoned with, and those afflicted with cancer. I came to know that desperation is stoked and fueled by the fear of not knowing. In prison, as it turned out, there was a lot of “not-knowing”.

Second, I had killed a man with my bare hands. In addition to this, I was a fairly large man, larger than most of the other inmates. Even though I garnered a small amount of respect from many of my fellow inmates due to my previous profession and what value that brought to them, I knew that no male lion ever got his choice of mate, or avoided the attacks of younger challengers due to his ability to draw the glycolysis pathway, make an incision look pretty, or read an X-ray.

Finally, I had killed within my same ethnic group. There is no need to belabor this point, but suffice it to say that there were three groups of prisoners that ate together, hung out together in the yard, and protected one another’s interests fiercely – the whites, the blacks, and the chicanos. During my third month a bad white cop had been brought into my cell block – one that killed four young unarmed Mexican-American boys, ranging in age from 10 to 14, literally children that he was strong-arming to sell drugs – forcing them to give him healthy cuts from the profits made in exchange for the favor of not arresting their parents and older siblings on fictitious charges. His trial had gotten a lot of attention in the media, and was a source of conversation on the inside long before he showed up. He was dead in four days – stabbed 40 times by a “shank” made out of a toothbrush and a coat hanger. In my first official medical consultation from the state of Texas as an inmate, two of the guards had dragged me out of my cell and into the yard to see if I could assist the guard performing CPR on him.

“How long have you been doing CPR,” I asked the guard, as I squatted down next to him. I noticed that I felt no particular emotion associated with asking. As was my habit, I began to compulsively count his compressions.

“Dunno… maybe twenty minutes…,” he answered, continuing to pump on the bare, bloody chest – the guard was paunchy, and short of breath from the exertion. His cap was perched way back on his boxy, crew-cut head, sweat was pouring down the sides of his face and increasingly darkening the armpits of his grey rayon shirt.

“Stop for a second,” I said. He did, and I felt for a carotid pulse – “nothing, start again.”

I reached up and lifted the inmate’s eyelid up and down, covering and exposing the pupil in an alternating fashion. I repeated it on the left. I could hear the guard wheezing next to me.

“I need to give him some mouth to mouth,” he said, his breathing was audible, and it was an obvious struggle to speak “its been a coupla minutes…”

I noticed that there was an abrasion on the inured inmate’s right temple, and significant swelling. I palpated the area and felt a depressed skull fracture – literally a golfball-sized piece of bone knocked out and down into the surface of the brain – pushed down at least an inch into the soft, light pink tissue of sentience lying below. I then looked down at his chest – almost all of the stab wounds were to the left of midline, just beneath his ribcage. I glanced reflexively at his neck veins – even though he was a stout guy, I could see them bulging under his skin. Whoever had done this was an accomplished killer – this guy had been rendered incapacitated by a blow to the head with some object which likely alone would have killed him, and then stabbed in the heart repeatedly and accurately. The distended neck veins meant that there was a lot of blood around his heart, trapped by the pericardium, or the tough but flexible sac surrounding the fleshy organ. It is well-known that one or more fairly small puncture wounds to the heart, if well-placed, can be more deadly than one large one. A large stab, one which makes a bigger opening in the heart muscle and the outer covering pericardial sac as well, allows the blood to empty completely from both the heart and the sac and into the larger surrounding chest cavity, but small ones may not. In this latter scenario, the blood escapes from the heart, but gets stuck in the sac in which it is enclosed. Once there is enough blood in the sac, it presses on the heart, and it can’t fill any longer with blood coming back from the brain above, and the other organs below – a condition we call “tamponade”.

If the heart can’t fill with blood, it can’t empty either, and no oxygen is distributed. One of my medical school professors, a trauma surgeon, was fond of saying during treatment of patients that were bleeding – “its not blood that’s important, son – its oxygen… its not the damn cars that keep the railroad in business – it’s the cargo”.

“You can stop now,” I said, “his pupils are fixed and dilated… he’s been dead for about ten minutes.”

So, there was a lot of “not knowing” in prison, but this was not to be confused with a lack of knowledge. There was a codex written in the cracks of the concrete walls of the prison cells and scratched just under the surface of the grassless recreation yard, and all had knowledge of this manuscript. In it was found a chapter with the details of what brought you in – who you were, and what you did and what that meant to those already there. In it was written as well the “rules” – the scriptures that mandated behaviors and traditions that had been a passed down, like genetic material, from generation to generation of the incarcerated – in it was written that if you kill a child, you will be killed – and if you kill a child of another race, you will be killed more quickly.

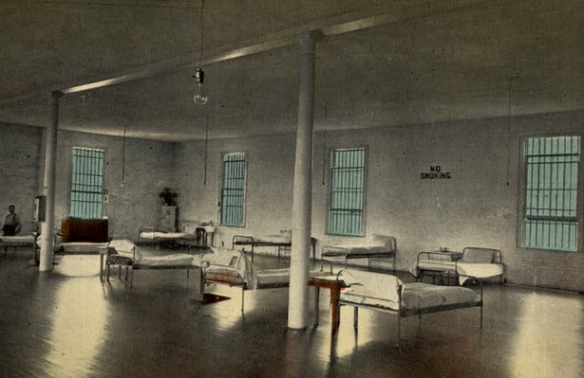

After about nine months, by which time I was determined to be a model inmate that caused no trouble, and attracted little, I was asked to begin to help out in the infirmary. At first I was ambivalent, but over time came to enjoy it as a means of passing time, and garnering additional favor with the other inmates and guards. The facility wasn’t too bad, actually. There was a little front room, where there was a desk and several filing cabinets in which inmate medical charts were kept, and a locked steel refrigerator with a small supply of common low-abuse potential drugs like antibiotics and insulin. Immediately behind this room were three reasonably equipped exam rooms, and farther back, a small open ward with six inpatient beds. The walls were bright white painted concrete blocks, and the floor was covered in pale green ceramic tiles – nothing fancy to look at, but a visual respite nonetheless from the grey walls, floors and bars of the cell blocks.

There was a prison doctor on-site every day, along with a male nurse on some days, and a guard. If there were patients that had to be kept overnight, a nurse would be called in on-call. Most of those that had to be kept overnight were the elderly inmates suffering the usual ravages of advanced age – most often pneumonia, exacerbations of emphysema, or heart failure. On occasion, we would keep someone there that had been involved in a fight and needed observation for a concussion or other similar injury. Not infrequently, we would recover inmates that had been sent “out” for surgery as well – most were transferred right from the hospital recovery room back to us at the prison infirmary – it was a lot cheaper for the state to recover them there than in an expensive hospital bed in Galveston or Houston. In addition to these relatively consistent players, there were a number of doctors-in-training that were in and out of the infirmary – mainly family practice residents from the medical school in Galveston. Some of these residents were “moonlighting” outside of the usual curriculum of the training program, called in when there were inpatients that required a bit more supervision, and getting paid for their time, and others were on “rotations” in prison medicine – completing electives of their choosing during the last year of training.

I did whatever was requested of me – I would see patients alongside the prison physician in the outpatient clinic, to speed up the schedule, and even though it wasn’t considered “legal”, at times he would ask me to see the last few clinic patients by myself so that he could leave early. Other times I would fill in with the inpatients when we had a full house, assisting the nurses or residents, and at times substituting for them when they couldn’t make it in for one reason or another.

After several years, I became a fixture there, and was allowed to opt out of a number of prison activities and the everyday singsong schedule of prison life as a result. It was a good deal for the warden as the on-call nursing and moonlighting residents were not needed as often, thus allowing him to pad the budget to the tune of what must have been a few thousand dollars each month. I was released from my cell in the morning, and basically spent the entire day down working in the clinic most days. I ate breakfast and lunch in the infirmary, and was able to schedule my rec time around the clinic’s schedule rather than the cell block’s, and therefore avoided a lot of daytime lockdowns, and other similar pleasures.

Rather than making life inside seem more reasonable; however, over time these liberties only served to increasingly remind me of what I had lost. It’s not the absence of freedom that leads to a desire to have more of it – ironically its just the opposite. Incarceration is not rehabilitative – it’s numbing and amnestic, and it creates a tolerance for more of the same. The problem with working in the clinic; however, was all the time I spent with those that were actually free to come and go. What evidently drove the inmates crazy at Alcatraz was not the rock itself, or even the isolation. It was the ability to look out of their cells and across the bay at beautiful downtown San Francisco, and when the wind blew in the right direction, to hear traffic noises, the ringing of church bells, and the merry sounds of those celebrating holidays. The doctor, visiting nurses and the trainees coming and going from the clinic were my own agonizing view of a figurative place across the water that I could see, but had no hope of reaching… or did I?

It was during this time that I decided that I would escape. I decided that I would use the same practice of medicine that I had used to gain access to this tormented place to free me once again.

§§§§§§

FIVE

My wife visited me one time – within a little more than one month of being incarcerated, and a little less than one month before the divorce papers came via prison mail. The conversation was short, terse and completely bereft of either eye contact, or emotion. Basically, it was a rundown of all of the financial travails I had left her to “fucking deal with alone.” All I could think of while she shared her morbid catalogue with me was “wow, she really loved me.”

My daughter didn’t say anything at all, lurking behind her mother at the table where we sat in the big open visiting area, alternating between nervous looks around the room at the other inmates and their visitors and then looking down at the concrete floor while chewing on her fingernails. But on leaving, she literally grabbed me and held me, her head on my chest and her eyes closed tight, for almost five minutes before my wife finally suggested, her arms crossed and her foot tapping, that “its time to go, honey… your father has to get back to whatever he does in here.” I could still feel my daughter’s small hands grasping my arms so tightly that those same fingernails, half covered in flaking pink nail polish, left indentations, and later, marks that lasted for two weeks. I would look at them every morning after she left, and run my hands up and down over the tiny dark red quarter-moon shapes. I would then go over and sit on the edge of my bunk for several minutes – trying to figure out what I was feeling. Was it sadness? Was it guilt? I wasn’t sure – at that point, I was just trying to remember what an emotion felt like without pharmacology involved.

She was too young to drive, so that incredibly pleasant visit with her mother was the last time I saw her. She wrote me religiously; however, despite the fact that that she had become a teenager, and was most likely experiencing all the emotions and parental loathing that I imagined had come with that. The letters were relatively short, mostly superficial and self-consumed, but she had kept at it – once a month most months, for more than five years.

It was about the time that I settled into work in the infirmary that I began to have dreams of my daughter. Actually they weren’t really dreams at all initially, just, well… flickerings – like what you might see from an old Super 8 projector sputtering on and off as the electricity supplying it was inconsistently applied, or perhaps the illuminating bulb was faltering and about to burn out. At first there were fleeting images of her as a baby, and then more substantial ones of her as a toddler, and then – full-blown dreams of her as an adolescent. It was funny – I was sure that the images were real, but I couldn’t really remember being consciously aware of any of them before these dreams – I didn’t remember noting any of this in real time, as it was happening over the past several years. The settings and some of the environmental details were familiar – I did have recall of some of those – things like the pattern on her nursery quilt, or perhaps the colors in her plaid private school skirt. It was her that I was missing – what I was missing were accessible memories of my daughter during my waking hours – they more or less didn’t exist, likely blanked out by my heavy drug use in addition to the work schedule of a busy academic surgeon.

However, these dreams were special, and I was intrigued by them… these dreams suggested that my subconscious had either done me an incredible favor, or perhaps played a cruel joke on me now that I was separated from my daughter – my subconscious had stored these memories away for me, safe from the drug-addled war zone of the rest of my mind – protecting images and vivid memories of her there. They were like a child placed into a storm shelter during a tornado, placed there so that I might be able to retrieve them later, safe and intact.

Then, on a night like any other, I had one that changed everything.

This time the memory was of her at the beach in Mexico – the last time I saw her before leaving and coming back to the States. I was sitting under a big white canvas umbrella, oblivious to the beauty of the Gulf and the pale yellow sand – drinking wine to try to stave off withdrawal, and scheming about how to get some Oxycontin. Although I was sleeping in my prison bunk, I knew that I had a waking memory of those things, but again those things only – the environment around her, but not her.

But in this dream, unlike in real time, I did see her there, standing on the beach. She was wearing a baggy green sweatshirt – it had been mine, but she loved it. I could see her face in profile – the perfect shape of her little nose and her long upturned lashes. She was looking at the ocean, and her form was motionless except for a few tendrils of hair – moving up and away from her face in the wind. It looked almost as if each tendril were alive, as if there was some sort of purposeful energy moving from the water, to the sand, and into her body. She turned to me and smiled, and I smiled back at her. I realized that even though I hadn’t been fully cognizant of her standing there in the moment, that my subconscious mind, and my soul clearly had. At that deeper level, I knew she was there, I “saw” her there, and loved her desperately.

I have to get out of here… I would not accept this sentence. I would not be able to wait until old age, to see her. I would not be willing to take the risk that I would die in here, like the old bastards I saw in the clinic every day, never seeing her at all. Something dormant within me had been reanimated – something emotional that had been locked away, like my physical being was now, by time and drugs and ambition and career.

I woke with a start, and sat up on the edge of my bed. My roommate shifted in his bunk above me, but didn’t awaken. I yawned and stretched and pondered again what I was feeling – if I was feeling anything, and knew immediately that this time I was, indeed. I put my head in my hands and sobbed quietly until wake up call, three hours later.

The harsh horn blast reverberated in the cell block at six a.m. sharp – bouncing off of the concrete surfaces and metal doors and eventually being reflected into the cells themselves, where they then rhythmically vibrated the hearing apparatus of my middle ear, transmitting a nervous signal to the part of my brain that processes and analyzes sound. If the neurons that did the final work of that analysis had been able to do so, they would have noted that a nearby group of other neurons, usually silent, were now firing rapidly, and purposefully – speaking to one another in muted sparks and whispers, laying down a new circuit, formulating a plan. Within a few days, and following a couple of trips to the library to study Texas maps, I was ready to move forward. Actually, the plan was three separate plans, arranged sequentially. First, I had to physically get out of the prison… second, I had to move through the Texas countryside south to the Gulf, and third, I had to leave the country. I was dangerously confident about the first two, but would have to figure out the details of the third on the fly.

The medical clinic would be able to provide me with the fulfillment of the first plan – getting out of the prison itself. For the second, I would rely in part on some intact pre-narcotic era experiences as a teenager that I could clearly remember – when I forded and canoed most of the Brazos River east and south of Houston to the Gulf. The “Brazos”, as most now referred to it, was originally named Los Brazos de Dios – The Arms of God. I wished at times, as I mulled the plan over and over again in my mind, laying in my lower bunk at night, that I didn’t actually know that obscure fact. It struck me that I perhaps didn’t deserve God’s embrace after all that had transpired, and therefore had made no plan to ask for it.

The doctors-in-training that visited the clinic had become more and more comfortable with me as time had passed with several cohorts of them, and would frequently smuggle things in at my request, like liquid soap, or various contraband food items. With my wife out of the picture, no one was sending me care packages filled with familiar items from home, and the local school kids didn’t tend to send cookies as often, with accompanying crayon-crafted cards, to guys that strangled people in gas station bathrooms like they did with the soldiers overseas.

I knew not to ask for anything that would bring attention to my relationship with them, because my liberties in the clinic could be revoked if someone became suspicious, and if I was yanked from the clinic, I didn’t know that I could come up with an alternate means of escape. When they arrived, two or three times a week, they always wore scrubs from the hospitals where they worked. I asked them for a couple of pair that would fit me, explaining that “they’re a lot more comfortable than these white canvas outfits”, and as well that “every now and then I’m forced to wear someone’s vomit for twenty-four hours, and this will allow me to change in and out of my regular prison whites while I’m down here.” I didn’t know if the prison doctors would be concerned about this, or if the guard that was stationed in the clinic daily would object either – there were no real individual fashion statements allowed in prison – there was only one uniform that inmates were supposed to wear, period.

Once they obliged, I started out by just wearing a scrub top every now and then with my prison-issued pants, and after noting no objections from anyone, added the scrub pants as well. Neither the guard, nor the clinic staff seemed to notice. The clinic had it’s own washer and dryer – making it easy for me to keep a pair clean at all times.

In addition to helping me and the clinic doctors wade through the usual work each day in the outpatient and inpatient areas, one of the residents would also often accompany inmates on the ambulance ride when they were transferred out to the two hospital facilities that were contracted car for them if we felt that they needed subspecialty care, or were too sick to keep in the facility. They called it a “ride out”. They were paid extra moonlighting fees for this. I had taken a particular interest in that activity, but not for financial reasons. As the residents were not there every day, some patients were transferred without a doctor accompanying them, and the staff doctors never themselves participated, the few hundred extra dollars not worth their time or trouble.

I had walked out to the waiting ambulance a few times with the residents, and noticed that the drivers and EMTs were almost never the same crew. I also noticed that they really didn’t pay attention to the residents themselves, just basically saying “hello”, half-listening to a cursory report about the patient being transported, and then closing the doors behind them after they each crawled up to sit on the metal bench next to the stretcher, where they immediately took out their cell phones and started looking at Facebook, rather than performing any real patient care. I had watched this process take place, and the ambulance leaving the premises perhaps twenty-five times – the guards at the two sequential gates would peer into the shaded windows to make sure the bay wasn’t filled with whites-wearing inmates, and then wave them on. I also noticed that on most of the ambulances, you were really unable to make out the features of anyone’s face when looking through those windows.

If I was going to go on my own “ride out”, several things would have to fall into place – we would need to transfer a prisoner out when there was no resident, the prisoner had to be either sick enough, or comatose enough to not know who I was. This would be difficult, as many of those that bounced in and out of the clinic on a regular basis had gotten to know me very well. Finally, there had to be a staff doctor in the clinic, or if not, we had to be at the end of a clinic day, with no more scheduled patients to see. The latter worried me a little, as only one of the three regular staff doctors bothered to stick around most days, the other two basically letting me do the work. If I were the only doctor on-site and there were patients scheduled after I went on a ride-out, they would discover me missing too quickly, and likely stop the ambulance. Last – I had to be out of the clinic proper, but accessible to the parking lot when the patient was transferred, or at least out of view of the guard, so that I could get into the vehicle without his observing me. It all seemed unlikely at times.

On a sun-drenched day in mid-May – when the cornfields in south Texas were filled with six-foot tall, sturdy green broad-leafed plants, and the thunderheads were just starting to roll over the flat coastal plains, fueled by the warm moist Gulf air moving up from the south, and the Midwestern cooler air moving down from the Edwards Plateau – it surprisingly all just happened to come together. It had been eight months since that fateful night when I decided that it was worth risking the possibility of never being released from prison, and even losing my life if necessary, to try to be with my daughter.

Joseph Cleveland Brown was an eighty-year old black man that had robbed a small Dallas bank in 1955, and in the process, had shot a security guard in the back, paralyzing him from the waist down. That was his ticket for a one-way ride with the Texas Department of Justice – a lifer. “JB”, as he was known affectionately, was one of the prison’s elderly mascots, a guy that everyone knew and loved. It was easy to love the old guys, as it turned out, because they weren’t a threat to anybody.

JB unfortunately had a bad case of Parkinson’s, and had been hospitalized in the clinic several times in the last two years with urinary tract infections. Like most men his age, he had a large prostate, and this obstructed his urethra from time to time, the tube that connected the bladder to the outside world. Other inmates with this problem had been taught to self-catheterize when necessary – to literally put a skinny soft plastic tube up through the penis and into the bladder to allow the urine to pass. JB was unable to do this; however, due the cruel “pill rolling” tremor that his neurologic disease had caused. The description of the tremor originated in the days when pharmacists and others used to “roll” pills from compounded ingredients, between the fingers and thumb. The hands of Parkinson’s patients look as if they are constantly rolling pills, or perhaps trying to snap their fingers to some demonic jazz tune that no one can hear. To make matters worse for JB, these tremors tended to intensify as any manual task was attempted, like inserting a catheter – an “intention tremor” in medical terms.

JB came into the clinic late in the day on a Monday, transported by wheelchair, and was in bad shape. He had a fever of 103, shaking chills, and was delirious – he didn’t know who he was, who we were, or what was happening to him. I got him into a bed and placed a catheter into his bladder – a torrent of turbid dark yellow blood-flecked fluid poured out of him – looking more like thin pus than urine. We got an IV started and some antibiotics, but he worsened overnight – the infection had likely spread up into one or both of his kidneys.

“I think he should be transferred, Dr. Phillips,” I commented to the prison doctor the next day – by chance, he was the one that always showed up and worked his own shift without sloughing off on me, “looks to me as if he’s heading for an intensive care unit somewhere.” Dr. Phillips came over and looked at his chart. “Fever still high, and urine output down since the catheter was placed… Hmmm… Creatinine up to 4.0… I agree, he’s in renal failure and flirting with full-blown sepsis. I’ll make the call downtown.”

I felt both sick and excited, but remained pokerfaced – I knew that this was my chance – there was supposed to be a resident from U.T. Galveston in that day to work with us, but he had called in and told us that he had been booked for ER duty there, and had forgotten. I watched and listened nervously, while Dr. Phillips made the call in the front office. Once he started talking, I walked over the medicine cabinet and took out a bottle of Ipecac syrup – the stuff we give to induce vomiting – used for instances such as when the occasional inmate tries to take an overdose of smuggled sleeping pills. I slipped it into the back pocket of my scrubs and took my shirt-tail out so that it would be covered. The guard on duty that day was an aging veteran who was nearing retirement – he had a lot of tenure, and got to pick his detail. He was in the clinic about twice a week as a result, where the work was easy and relatively safe. I had noticed over the past few months that he was constantly nursing a cup of coffee, and so I made him a pot in the tiny galley in the clinic each day first thing when I saw him on the schedule. He had walked over to see JB and was trying to talk with him – they had known one another for more than thirty years. While he was standing at the bedside at one end of the clinic, and Phillips was still on the phone on the other, I walked over and put some Ipecac into his coffee cup.

Phillips hung up, and the guard walked back over to his perch in the corner of the inpatient ward and sat down. JB hadn’t answered any of his questions – he was barely conscious and mumbling under his breath something unintelligible. “Looks like that there aren’t any more outpatients today,” I said casually, looking at the paper schedule that was tacked up to the bulletin board. I think I’ll take a walk around the yard, if that’s okay with you guys, and go back to the cell block.” “Fine with me docky,” the guard said. He pushed his cap back on his head and rubbed his ruddy forehead with his slightly deformed arthritic, I thought to myself, never really noticed before… fingers, then waved me off, “have a good one, docky, see you later in the week.” I had done this a hundred times before – there was absolutely nothing for him to be suspicious of. “See you next time,” Dr. Phillips said, who by now had hung up the 1950’s era black landline receiver on its receptacle, and strode over to the desk where he had plopped his briefcase, “I’m getting out of here too.” He picked up his things, strode over the front door that opened directly onto the gravel-filled parking area, and then he was gone.

I nonchalantly walked out the side door of the clinic, where there was a short covered walkway leading to a small adjacent supply building – out of line of site from the guard tower, and not likely to be traveled by anyone. About the time I heard the guard inside retching, the local ambulance service showed up. Damn… perfect timing, I whispered. I stood and watched the EMT and the driver walk in the clinic front door, and then come back out about ten minutes later wheeling JB out on metal stretcher with wheels.

“Did you get a load of that old guard?” I overheard the driver ask the EMT.

“Yeah, he looks pretty bad, maybe we should grab him and wheel him out next – poor bastard,” he laughed.

I had never seen either of them before.

I strolled over just as they were about to close the back door of the ambulance.

“Mind if I do a ride out with you guys?”

“You the resident?” the EMT asked, suspiciously, “aren’t you a little old?” He looked me up and down, and the driver moved a couple of steps back and looked at one of the distant observation towers – the only one that had a clear view of this small parking area. I knew that one of the guards in that tower would notice the hesitation, and the driver’s nervous gaze, if we stood there for more than a few more precious moments.

“Yeah,” I replied quickly, resisting the urge to look up at the tower, my heart pounding, “you know… second career thing – first one didn’t work out so well”

“Yeah? What was that, doc?” the EMT asked.

“Uh… I was working a lot with pharmaceuticals”

“Whatever,” he grunted, “hell of a thing to do at your age, training to be a doc – I would have picked something easier – like maybe ditch-digging. Yeah sure, come on, I can sit up front with my buddy here and you can hold this old fart’s hand. He smells like shit.”

He looked over at the driver, who just shrugged his shoulders.

I climbed up next to JB, and sat on the metal bench next to him in the little area cleared for that purpose, an oxygen tank to my left and several clear plastic bags containing various emergency medical supplies hanging from a metal mesh rack bolted to the wall on my right. The EMT slammed the door shut, and I listened to the gravel in the parking lot crunch under their feet, as he and the driver walked to and opened their respective doors. I noticed that I was holding my breath as I counted their steps, four… five… six… seven… eight…

I looked down at JB – he had been basically comatose now for almost forty-eight hours. I exhaled, slowly, and even allowed myself a little chuckle.

The driver started the ambulance, and as it shifted into drive, there was a jolt, and the stretcher jerked violently a few inches forward and then back – its loosely-latched metal rails rattling loudly. JB opened his eyes for the first time in two days, propped himself up on his right elbow and looked directly at me, startled. In the small space of the ambulance bay, his face was only about eight inches from mine. We were friends – he even called me “Docky Joe”. I looked back into his bloodshot eyes, and his sweaty face, and froze. This could screw everything up… He squinted, and his deep gravely voice boomed, “Mabel? That you baby?” His expression then changed quickly from confused, to blank, and then relaxed. He laid back down and shut his eyes – smiling. Right before he lapsed again into his fevered slumber he added, while smacking his lips – “Sho was some good cookin’ – you got any more of them pork chops handy sweetie pie?”

I swallowed hard, and regained my composure. With my back to the window, I leaned over JB as the ambulance moved slowly forward, acting is if I were checking the intravenous line in his right forearm.

We stopped twice to let the guards peer in through the frosted glass, and then JB, Mabel and I were on the road. I counted the telephone poles as they passed by out the window.

§§§§§§

SIX

When we were about twenty minutes out, I allowed myself to lean back, and peer out of the window. JB was stable – the portable ECG machine clamped to the stretcher showed a normal heart rate, and the automatic blood pressure cuff readout was good. I reflexively felt his forehead – he was febrile – but not more than 101 or so, I thought to myself.

We would either shoot into Houston, or we would go around the south side by way of the Beltway, hit I-45 and go all the way down to Galveston – to one of the two hospitals that had a contract with the Texas Department of Justice to provide advanced care for inmates. However, I would not be making the trip to either one of them if possible.

I tapped on the window to the cab, above the head of the stretcher, and the EMT slid open the glass.

“What’s up doc?” he asked.

I tapped my scrub pocket, as if something were there.

“My wife just texted me, and wants to know where she should pick me up.”

“Tell her that she can catch us at Rick’s Men’s Club at about 2 am…” he replied. He and the driver laughed. “We’re heading down to UTMB in Galveston doc, that okay?”

“You know… we live in Pasadena,” I replied, “unfortunately, we can’t afford to live inside the loop on a resident’s pay… could you drop me somewhere between Houston and Galveston, so that she doesn’t have to drive all the way down to the island with the kids after school to get me?”

He looked at me and shook his head, “speaking of pay… you know you won’t get any dough for the ride out, doc, if you don’t stay with us and the patient all the way to the hospital, right? It’s the rule – I didn’t make it, but all the same…”“Yeah,” I replied, “I know, but keeping the little lady happy is worth more to me – I’m… just trying to stay out of jail, if you know what I mean.” “No shit!” he replied, laughing again. He tapped on the wedding band on his left hand, which was grasping the windowsill, and then leaned over and mumbled something to the driver. “Can we drop you at the corner of the Beltway and I-45?” he asked, “there’s some gas stations and stuff there.”

“Perfect,” I answered, “I’ll text her in a minute and let her know.” “No problem…,” his expression turned serious, “you know doc, she must be an angel to let you do something like this at your age. And you got kids too?” “Yeah, I replied, “she’s great – literally lets me get away with everything – just short of murder I guess…” He winked and closed the window, and we snaked methodically through the south Houston traffic. Forty-five minutes later, we pulled off the highway, and into a convenience store parking lot at the planned drop off.

The EMT jumped out, came around back and opened the door. “You see her yet? She here?” he asked, looking around. “No, she won’t be here for another fifteen or twenty minutes, but it’s no sweat, really.” I patted JB on the forehead, and clambered out the back. “He’s stable right now. His BP dropped to the eighties for a little while, and I gave him a 500 cc bolus of saline – came right back up.”

“You chart it?” he asked.

“Yessir,” I replied.

He pulled himself up onto the seat where I had been, and gave me a salute – I noticed with some relief that the driver hadn’t stopped the engine. “Seems like you like this guy. Don’t worry, we’ll get this old geezer down there safe and sound – that’s what we do… see you on next ride out, doc,” he said. I smiled, waved, and shut the back door. They eased out of the parking lot, and onto the service road. I looked over my shoulder once they were out of vision, and through the big plate glass windows of the convenience store. There was a digital clock with giant red numerals, embedded in the middle of an elaborate Budweiser sign bolted to the wall above the refrigerator case, replete with Clydesdales and two giant illuminated plastic cans of beer. It was five o’clock. Under the usual circumstances, I would still be in the clinic. The only guy that knew I left early was the guard that had drank the ipecac – it was a good, if not sure bet that he had gone home before his shift was up. When dinner started at six, I might be missed, but at times the clinic ran into the dinner hour when we were really busy. But after dinner… by seven o’clock at cellblock check-in – I definitely would.

My plan was to steal a car, if I could, and get out into the country about thirty or so miles east of here, where I would then set out on foot. There was a lot of desolate farm country in that area, and I was going to try to make it to the Brazos River that way – I knew that I was much less likely to be caught than if I tried to drive all the way to the coast, or to Mexico – those two approaches were completely predictable. I also knew that it was Spring, and with the corn and alfalfa was all grown up and awaiting harvest – higher than a man’s head, that I could hide from helicopters if they came searching. This part of the world was flat as a pancake, and you could hear the rotors for miles. However, I knew that they probably wouldn’t – the state troopers and local law enforcement would be looking for me in a car, or trying to hide out anonymously in the city.

The convenience store was busy, and looked relatively new. There were three separate islands for self –serve gas, one each in front, and to the left and right of the store itself, with four pumps at each island. There must have been ten cars in various states of either being actively fueled, or awaiting the return of their occupants – inside paying for gas, or buying something. I walked inside, nonchalantly, and picked up two cans of Vienna sausage, and a large Coke – I had five dollars total, and needed calories – it might be a while before I got to eat again. After I took my turn in line, I scanned the lot. I watched as an elderly woman with an impressive towering grey bouffant hairdo methodically pumped gas into her late-model white Toyota Camry, put the nozzle back into the receptacle, and then walked ever-so-slowly, with the assistance of one of those three-rubber footed aluminum canes, into the store. I took a big swig of my coke and walked past her casually. She smiled as she passed. I just kept walking toward the island where her car was located, as if my own was there. I turned and glanced over my shoulder, and saw that she was heading in the direction of the bathrooms in the back of the store. She’ll be in there for a while, I thought to myself.

I picked up my pace, and reached the passenger window of her car. As I had hoped, the keys, with a small plastic picture frame dangling from the ring – no doubt sporting a favorite grandchild photo, were in the ignition. No one was paying me any mind whatsoever – the Houston area is the medical-care capital of the world, and every day there are thousands and thousands of people walking around in scrubs – in the shopping malls, at gas stations and convenience stores, everywhere…

I capped my soda, walked around and slipped into the car, tossing the bottle the plastic bag containing my precious high-fat meal onto the passenger seat. A somewhat dated cell phone was sitting in one of the drink holders – I grabbed it, turned it off, and then tossed it out the window and into a trashcan. I started up the car and drove slowly out of the lot, onto the service road. I had lowered all of the windows so that I would know if anyone in the had discovered me and was yelling at me to stop…

Does that ever work, does anyone stealing a car ever really stop when they yell “stop”?

Nothing.

The rush hour traffic heading down to Galveston was bad, and that made me a little nervous – but I took some modest comfort in the fact that there were more than twenty thousand cars stolen in Houston each year, and the police didn’t get too worked up about them in real time. I figured it would take the old lady more than twenty minutes to get in and out of the bathroom, maybe buy an item or two, and finally discover her car was gone. It might be close to thirty before the police were even called about it, and then they would have to get there in the same traffic that I was driving in if they were going to actually take a report. I should be getting off of the interstate by then.

I was finishing the second can of Vienna sausage when I turned off of the I-45 and onto a sparsely traveled two-lane farm-to-market road – heading west.

§§§§§§

SEVEN